Conditionals¶

Consider the following function, which, given a price and quantity, calculates a total cost with a 5% discount:

(defn total-cost [price qty]

(let [discount 0.05]

(* price qty (- 1 discount))))

All well and good, but that’s not an entirely realistic scenario. What about a business that bases discount on the quantity purchased? For example, if you order less than 50 items, you get a 5% discount; otherwise (when you order 50 or more), you get a 7.5% discount. This is something you haven’t seen yet—calculations based on some condition being true or not.

Testing conditions: if¶

To accomplish tasks like this, you need ClojureScript’s if function[1]

The model for an if is:

(if condition true-expression false-expression)

The condition is some expression whose value is either true or false. If the condition is true, the value of the entire expression is true-expression; otherwise, the value is false-expression. Going from this abstract explanation to the concrete example of the discount:

(if (< qty 50) 0.05 0.075)

The expression (< qty 50) tests to see if qty is less than 50. If so, the value of the expression is true, so the result of the expressions is 0.05; if not, it’s false, and the value of the expression is 0.075.

Note

If you simply enter an if expression such as the preceding one into an active code area, you will not see any result. This is due to the way that

ClojureScript in the browser works. It will do the right thing when used in a program.

Let’s see how this works in a program. I have moved the code for calculating the discount into its own function because calculating the discount is really its own separate task. How you figure out what the discount is doesn’t change the formula that uses that amount. Try changing the quantity (the 30 in the last line) and see how that affects the total cost.

Functions that test conditions¶

ClojureScript defines these functions for testing conditions.

All these functions return true or false as their value; all of these examples will evaluate to true.

| Function | Means | Example |

|---|---|---|

| < | less than | (< 3 5) |

| <= | less than or equal | (<= 19 45) |

| > | greater than | (> 17 9) |

| >= | greater than or equal | (>= 25 25) |

| = | equal | (= 10 (/ 20 2)) |

| not= | not equal | (not= 17 3) |

Sequences of conditions: cond¶

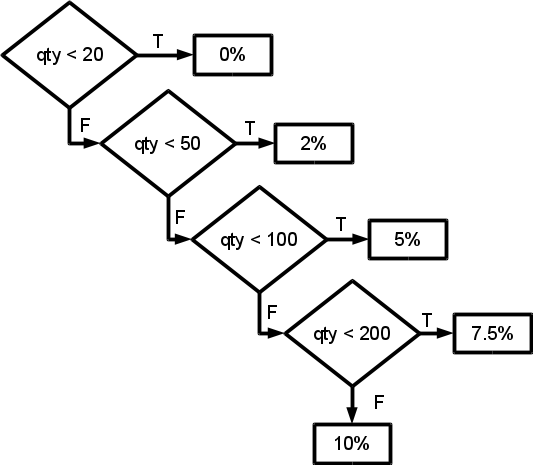

What happens if you want multiple levels of discount depending upon quantity?

| Quantity | Discount |

|---|---|

| < 20 | 0% |

| < 50 | 2% |

| < 100 | 5% |

| < 200 | 7.5% |

| >= 200 | 10% |

You can represent it in a flowchart form like this:

Note

In the second diamond of the flowchart, you don’t have to ask if the quantity is greater than or equal to 20. You already know that, because the answer to “is it less than 20?” came back as “no” (false).

You could write it this way in ClojureScript:

(defn calc-discount [qty]

(if (< qty 20) 0

(if (< qty 50) 0.02

(if (< qty 100) 0.05

(if (< qty 200) 0.075 0.10)))))

But that’s really difficult to read, and with a few more choices, the indenting and closing parentheses would get pretty deep. For situations such as this, ClojureScript provides the cond construct, which is followed by pairs of conditions and values. ClojureScript tests the conditions one at a time and yields the value for the first condition that evaluates to true. Here is what the discount function looks like using cond; try changing the quantity in the function call and see that it works correctly.

The value for the last test, :else, is chosen if none of the other conditions came out true.

There is no law that says all the conditions must test the same variable. Consider a cinema that charges $4.00 at all times for children under age 10, $6.00 all day on Mondays (day 1 of the week), $7.50 before 3 p.m. and $8.50 after that on all other days of the week.

(defn ticket-price [age day hour]

(cond

(< age 10) 4.00

(= day 1) 6.00

(<= hour 14) 7.50

:else 8.50))

Compound conditions: and and or¶

Consider these modifications to the pricing conditions:

- Price is $4.00 if the person is less than 10 years old or 65+ years old.

- Price is $6.00 if the day is Monday or Tuesday or Thursday.

- Price is $7.50 if the hour is after noon and before 3 p.m.

To handle these compound conditions, ClojureScript provides the and and or functions, with this model:

(and condition1 condition2) (or condition1 condition2)

The result of and is true when all the conditions evaluate to true (think “both condition1 and condition2”). The result of or is true when any of the conditions evaluate to true (think “either condition1 or condition2”). You may test more than two conditions with and/or.

Try calling the following ticket-price function with various ages, days, and hours to see the compound conditions in action. In this code, Monday is day 1 and Sunday is day 7.

When evaluating and/or, the conditions are evaluated from left to right. ClojureScript will stop evaluating expressions as soon as it knows for sure what the final result has to be. For example, with and, since all the conditions have to be true, as soon as a condition comes back false, there’s no need to look at the other conditions. Similarly, with or, since the whole expression is true if any condition is true, ClojureScript can stop testing conditions as soon as it finds a true condition. The name for this behavior is “early exit.”

When would you use this? Here’s a scenario: you are given a number of items and the total price for all the items, and you want to know if the average price is more than $7.00. You can write a compound condition like this:

(and (> n 0) (> (/ total-price n) 7))

What happens if n is zero? Without early exit, you’d be in trouble. ClojureScript would evaluate both conditions and try to divide by zero when evaluating the second condition. However, with early exit, because n (zero) is not greater than zero, the first condition comes back false, and ClojureScript can stop—the whole result has to be false, and the division by n never happens.

The not function¶

Rounding out the boolean functions is not, used in this model:

(not condition)

When the condition is true, not changes it to false; when the condition is false, not changes it to true. So, if I wanted an expression to be true for anyone who is not between the ages of 18 and 21, I could write:

(not (and (>= age 18) (<= age 21)))

I could also write it this way:

(or (< age 18) (> age 21))

but the first way expresses the logic more closely to the way we think and talk about the condition.

You may have noticed that when I got rid of the not, the and changed to an or, and the conditions switched from >= and <= to their opposites. This is an application of the DeMorgan Laws, which tell you how to convert compound expressions with not:

(not (and a b)) → (or (not a) (not b)) (not (or a b)) → (and (not a) (not b))

Use these conversions when you need to write a compound condition in a way that corresponds to the logic of the transformation you are doing.

Here is a video about the DeMorgan laws; it was originally designed for a course in the Ruby programming language, but the principle applies.

Exercises¶

Write a function named calculate-pay that calculates a person’s total weekly pay, given the hourly pay rate and number of hours worked per week. If a person

works more than 40 hours, they get “time and a half”; that is, 1.5 times the normal pay rate for the hours above 40.

Write a function named valid-triangle that takes the lengths of the three sides of a triangle and returns true if a triangle with those sides could exist, false otherwise. A triangle is valid if the sum of any two sides is greater than the length of the remaining side. Thus, a triangle with sides of length 3, 4, and 5 is valid because 3 + 4 is greater than 5, 3 + 5 is greater than 4, and 4 + 5 is greater than 3. A triangle with sides 2, 7, and 11 is impossible because 2 + 7 is less than 11.

This function does the job, but it can be improved. See the next tab for a better version.

The (and...) expression already gives you a value of true or false, depending on the

arguments. There is no reason to use if to return the value; instead, evaluate the expression and

use that as the function value.

Write a function named calculate-tax that takes a person’s annual income as its single argument and returns that amount of tax the person must pay.

Use cond in your solution. Tax is calculated according to the following table:

| Income | Tax |

|---|---|

| <= 10000 | 0 |

| <= 30000 | 5% of amount over 10000 |

| <= 70000 | 1000 + 15% of amount over 30000 |

| <= 150000 | 7000 + 30% of amount over 70000 |

| > 150000 | 31000 + 40% of amount over 150000 |

| [1] | if is technically not a function. In truth if, def, let (and others) are classified as special forms. defn is also not a function; it is a macro. At this stage, these are distinctions without a difference, but they will become important if you go in depth with ClojureScript. The only reason this footnote is here is so that outraged language purists won’t bombard me with emails about my obvious misclassification of if. |