In this series of articles, you will learn how to use the ODFDOM Toolkit API to create documents in OpenDocument format (ODF) and extract information from ODF files.

Before looking at the toolkit, let’s talk about OpenDocument format. The best way to do this is to look at a sample word processing file (see a screenshot). At its heart, an OpenDocument file is a .zip file that contains XML files that describe the document. If you unzip the sample document, you’ll get about a dozen files and directories. Here are the most important ones, and how they relate to your document.

The manifest.xml file is the “table of contents” of the document package. It contains a list of all the directories and files that make up the ODF document, not including itself. The ODF toolkit builds the manifest file for you automatically when you create or modify a document.

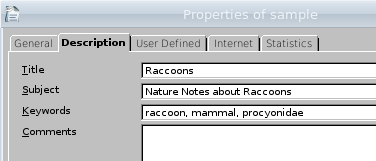

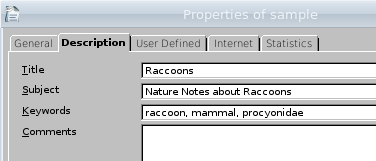

The meta.xml file contains meta data about the document. It gives you information such as creation date, author, and description. For example, the information shown in this dialog box is reflected in this XML:

|

<dc:title>Raccoons</dc:title>

<dc:subject>Nature Notes about Raccoons</dc:subject>

<meta:keyword>raccoon</meta:keyword>

<meta:keyword>mammal</meta:keyword>

<meta:keyword>procyonidae</meta:keyword>

|

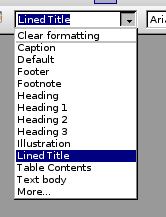

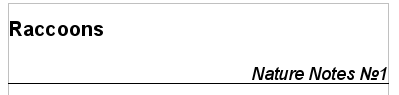

The styles.xml file contains information about named styles; the ones you see in a dialog box in your word processor. The following screenshot shows this dialog along with the two headings from the sample document, which are in Heading 1 and Lined Title styles.

Here is the XML for the Lined Title style, edited for purposes of brevity.

Every style belongs to a family. The family tells

what kind of element this style is applied to. Styles for paragraphs

or headings belong to the Paragraph family; styles

for inline text belong to the Text family.

The style also has a style:name attribute for internal use and a

style:display-name attribute to show to the user. The convention is

to change blanks in the display name to _20_ in the internal style

name.

Within the style object are the style properties that describe what the style looks like. These properties come in property sets, and a style can have properties from more than one set. The Lined Title style has paragraph properties to set the text alignment and borders; its text properties, which apply to individual characters, specify the font name, font size, and font style.

The styles.xml file also contains automatic styles. These styles have an internal style name, but are not accessible to users by name. For exampe, when you specify the date field at the lower right of the page, its style is automatically created with the rather prosaic name of N37; here is its XML.

The style for the page layout is also in the automatic styles.

The text of those two headings (and the blank line between them)

goes into the content.xml file with the

following XML; <text:h> specifies a heading and

<text:p> a paragraph.

When you click the “bold” or “italic” icons in the word processor, the program will produce an automatic style for the selected text. These automatic styles go into the content.xml file; they have the same format as the styles in the styles.xml file. Here is the relevant XML for the styles and the text that uses them:

|

<style:style style:name="T2" style:family="text">

<style:text-properties fo:font-weight="bold"/>

</style:style>

<style:style style:name="T4" style:family="text">

<style:text-properties fo:font-style="italic"/>

</style:style>

<text:p text:style-name="Standard">Raccoons, those

mysterious masked mammals, are members of the

<text:span text:style-name="T2">procyonidae</text:span> family.

The scientific name for the raccoon is

<text:span text:style-name="T4">Procyon lotor</text:span>

|

Images are referred to by the <draw:image> element, and the image

itself is placed in the Pictures folder. The ODF Toolkit lets you insert

both the image and the XML with a call to a single method.

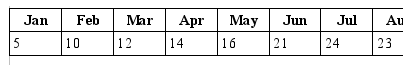

Tables are specified in the content file with a

<table:table> element. The table starts by specifying each

<table:table-column>’s style. The column specifications

are followed by <table:table-row> elements. Each row

contains

<table:table-cell> elements, which in turn contain the

cell content. In the case of this table, each cell contains a

<text:p> element for the number of raccoon sightings.

The chart is considered to be an object; it is referenced by a

<draw:object> element that has an

xlink:href attribute that refers to the Object 1

subdirectory. That directory contains its own

content.xml and styles.xml files.

I could go on at great length about the XML that makes up an OpenDocument file, but let’s face it—nobody wants to work at the level of .zip files and raw XML. Instead, use the ODFDOM Toolkit, a set of Java classes that makes creating and modifying documents much easier.

The ODFDOM classes allow you to work with a document at three levels, as described on the project’s site:

In the next article, we will use the ODFDOM classes to convert an XML data file of information about movies to an OpenDocument text (word processing) file.